9. Wedding Bells and Bureaucracy

Did a patent lawyer’s love life determine the course of industrial policy in postwar Germany? With the departures of both Draper and Martin, Phillips Hawkins suddenly found himself in charge.

Recap: Germany’s hyper-concentrated death star economy fueled Hitler’s rise to power and the outbreak of WWII, so U.S. postwar policy prioritized economic decentralization in parallel with democratic political reforms. Yet on the ground, General William H. Draper, Jr. recruited bankers and big businessmen to run the “economic side of the occupation.” After the first two decentralization leaders resigned in frustration, an experienced investigator was brought in. Alas, forces both inside and outside military government were thwarting progress even though the military governor understood the importance of decentralization. Another Allied Power shared some blame for gridlocked negotiations. Then the midterm elections of 1946 shifted the balance of power domestically. But in the summer of 1947, two leaders abruptly departed Germany: the biggest roadblock to reform and the strongest advocate for it. Without them, would reform get back on course– or further derailed?

Uptown Girl

Your first guess might be that Phillip Hawkins fell in love with some beautiful fräulein– perhaps the daughter of some prominent German industrialist– and that prompted a change of heart towards his duties.

After all, until 1947, there were few signs that Hawkins was not aligned with official American policy. Yes, he had been a patent lawyer for a chemical and munitions manufacturer before the war. But James Stewart Martin had found Hawkins to be a hardworking and loyal deputy. When Hawkins stepped up to serve as acting Chief of the Decartelization Branch while Martin went back to America for several months in late Spring 1947, longtime staffers who hailed from the Department of Justice were encouraged that Hawkins implemented their suggestions for making constructive organizational changes to the Decartelization Branch.

Martin’s resignation also put a degree of pressure on OMGUS. The New York Times reported his allegations that “the expressed wishes of the American people are being over-ridden by special interest groups who have their own idea of how Germany ought to be treated.”

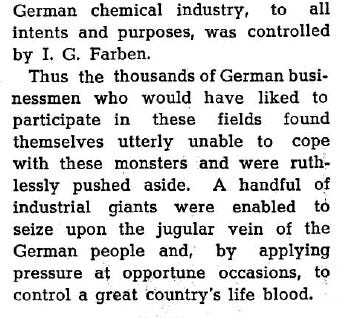

Later that year, Hawkins would even publish an article in the OMGUS Weekly Information Bulletin extolling the virtues of the new Military Government Law No. 56. The ardent imagery would have made a serviceable alt-caption for anti-monopoly political cartoons from the Standard Oil era. Hawkins wrote, for example, that the law was designed to:

“[B]reak the strangle hold which cartels, combines, syndicates, trusts, and other excessive concentrations of economic power inflicted on the German people. It endeavors, once and for all, to smash these octopuses which obstruct the upward surge of a healthy economy for all and enchain the very right to existence of the individual.”

Indeed, Hawkins framed Law No. 56 as a charter of economic liberty: The “small businessman” would soon be able to “establish an enterprise anywhere he chooses, to produce or sell whatever he wishes, to sell to whomever he desires, to charge less to the consumer if he sees fit, free from the dictates of the economic giants. It will not be permitted for him to be driven to the wall, discriminated against, dictated to, and forced out of business completely by the ruthless practices common to cartels, combines, syndicates, and the like.”

Hawkins contrasted this vision with Soviet-controlled trusts that were “driving the independent German businessman out of business… at a time when Germany has need for all the independent initiative, energy, and talent that she can muster.”

Yet despite championing vigorous enforcement of the new law, Hawkins acquiesced to the adoption of implementing procedures that would make effective enforcement difficult in practice. The Economics Division ensured that Law 56 provided expansive procedural protections for firms. Even if ordered to disperse, firms would have an opportunity to file objections and submit their own plans for implementing breakups.

The Chief of the Enforcement Section of the Decartelization Branch, Johnston Avery, later called the resulting procedure, which accumulated more and more steps and reviewers over time, “a masterpiece of confusion.”

Another key problem was that “virtually all decartelization work” was put “in the hands of the Germans,” rather than the Decartelization Branch. According to The New York Times:

“In each of the eight states in the two zones is a German commission and a United States or British counterpart. The German commission writes the directive for breaking up a particular cartel, which then goes to a German bi-zonal commission in Frankfort on the Main for review. The German agency passes it on to a bipartite military government commission, also in Frankfort, for coordination with other affected agencies.”

Ultimately, the final procedures “took the authority for deconcentration out of the hands of the Decartelization Branch and placed it in the hands of two review boards [staffed by] other agencies of OMGUS.” Every member of Avery’s staff (five lawyers and three investigators) complained to him that it would be “impossible ever to break up a German monopoly under that procedure.”

One staffer wrote an outline on “The Ineffectiveness of Law 56,” which among many concerns noted that “[f]inal say lies in a board which most likely will consist of business men prejudiced against decartelization.”

Indeed, one staffer calculated that “if the German enterprise took advantage of every step provided, it would take more than two years before we reached the point of ordering a dissolution, if, indeed, we ever reached that point.” If a German combine exploited every extension and appeal allowed by the process, the earliest final decision could not be reached until after the next U.S. election for President—which the Economics Division (confidently, but wrongly) assumed would flip to a Republican. With multiple layers of review before the equivalent of a complaint could be filed, the procedural rights exceeded those granted to corporate defendants in the U.S.

“If I let you write the substance and you let me write the procedure, I'll screw you every time.”

– Congressman John Dingell (much later in history)

When Avery pushed back against the impracticality of the procedures, the most he “could get out of Mr. Hawkins was, ‘that is the way General Draper wants it.’”

Why did Hawkins react that way?

Perhaps because he was about to marry a woman named Dorothy Wagner.

Hawkins likely met her in Germany, and they wed in Berlin, but she was American.

Like Hawkins, she had already been married once before, to a navy lieutenant who was killed near the Normandy Coast the day after D-Day.

So Dorothy’s maiden name was not Wagner.

It was, instead, Draper.

Thus, William H. Draper, Junior became Hawkins’ father-in-law on July 15, 1947.

Another Man Develops a Plan

Meanwhile, American foreign policy was changing. Although a cost-cutting mentality had begun taking hold, especially after the midterm elections, some American businessmen and politicians started to think there might be value in making longer term public investments in Europe.

In June 1947, Secretary of State, General George C. Marshall gave a speech proposing the fundamental elements of what would eventually become the Marshall Plan to fund the reconstruction of Europe. Political winds soon shifted towards boosting German production, combatting shortages, and rebuilding Germany as a bulwark against the Soviets.

But this emerging elite consensus favored changes beyond increasing investment. By August 1947, Secretary of Commerce Averell Harriman—then one of the wealthiest men in the country, as heir to a railroad baron’s fortune and the founder of a Wall Street investment bank with ties to Nazi industrial magnate Fritz Thyssen– was urging Truman that “[t]here must be an end to denazification at an early date to release these people, many of them the best brains in the country, to go back to their productive activities.” By that fall, at the request of the State Department, OMGUS started pressuring local German governments to adopt more lenient classifications for Nazi offense, and expedite clearances.

Similarly, Harriman agitated for termination of decartelization, echoing the findings of other business delegations that passed through the Economics Division, that the decartelization program constituted “impractical pulverization.” At some point that summer or fall, the Decartelization Branch suffered personnel cuts.

Nonetheless, on paper, decentralization policy remained consistent. When a revised version of the Joint Chiefs of Staff order was issued in July 1947, many sections were substantially changed, primarily to reflect the defeat of Morgenthau’s hard peace. But the decentralization provisions emerged from this process unscathed. Perhaps this simply reflected an acknowledgment that an express change would conflict with the views of both the State Department and President Truman, but given General Clay’s demonstrated ability to influence the Secretary of State, it seems unlikely the provisions would have escaped any significant changes or new caveats if Clay were strongly opposed to the policy. Instead, JCS 1779 still directed OMGUS to promote “dispersion of ownership and control of German industry.”1

And President Truman’s stance remained clear. He advocated the same principles for international trade generally in a March 1947 speech, declaring that the “pattern of international trade that is most conducive to freedom of enterprise is one in which the major decisions are made, not by governments, but by private buyers and sellers, under conditions of active competition, and with proper safeguards against the establishment of monopolies and cartels.” Then in October, Truman’s DOJ filed an antitrust lawsuit against several investment banks– including Draper’s former employer Dillon, Read & Co.

Hawkins may have found himself caught between Draper– who was back in America, but now close family, and Clay, Hawkins’ ultimate boss in Germany. Hawkins was promoted to Deputy Director of the Economics Division in September 1947. In October, perhaps in response to critical press scrutiny, Hawkins announced that the German government had been directed to “sell at once eight coal distributing companies in an effort to remove them from the giant Ruhr mining cartels,” with an aim “to divorce the distributing companies from the mines.”

What About The Germans?

Hawkins’ article– published in November 1947– was certainly more aligned with Clay’s views– or at least Clay’s media sensibilities– than Draper’s. In the article, Hawkins not only embraced official policy, but expressed a degree of optimism about its feasibility. He argued that decentralization was not a “new” idea: “Germans have been fighting monopolies for generations– under the Kaiser; under the Weimar Republic; in short, ever since industry became the backbone of the German economy. However, the forces which the large-scale monopolies could muster were too strong and too unscrupulous.” But fortunately, “the German and US governmental authorities [were now] united in a common desire to see that the law succeeds.”

This subtly pushed back on a favorite line of attack by the Economic Division– echoed by the anonymous “top business executives” whose May 1947 press release argued for delaying decartelization, which represented “economic principles quite new to the German mind.”

But did they have a point?

What did the Germans think about all this, anyway?

And did it matter who Hawkins chose as his best man for the wedding?

Stay tuned for the next installment…

Primary Sources

Because archive.org was (yikes!) hacked, this post does not link to any newly-scanned primary sources (yet).

Part of my goal with this project is to facilitate renewed scholarship into this era, so I plan to post more scans to Internet Archive— however, to minimize spoilers, I’ll wait to post some of them until later in the series. I’ll also provide a list of some excellent secondary sources...

In his memoir, James Stewart Martin wrote that the Attorney General told him after a Cabinet meeting that the members “had seen no reason for changing the government’s policy on decartelization.”

Oh my god I literally gasped — the fucking Drapers, man