1. How the "Grandpa of the VC Industry" Sabotaged the Rule of (Antitrust) Law in Postwar Germany and Japan

Introducing an Urbane Workaholic Banker-Magician-Soldier

After WWII, U.S. occupation governments had clear mandates to spread economy democracy in Germany and Japan. But implementation fell short of their aspirations. Why? And what did the “Grandpa of the VC industry” have to do with what some headlines called “sabotage”?

1. An Urbane Workaholic Banker-Magician-Soldier

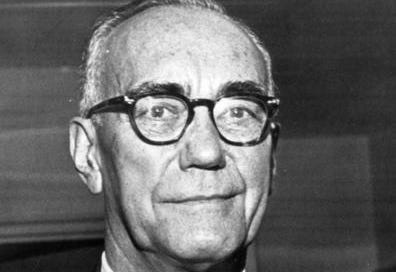

Today, at least on the West Coast, General William Henry Draper, Junior may be best known for founding Silicon Valley’s first venture capital firm Draper, Gaither & Anderson in 1959.1 His son Bill was a widely respected early investor in Skype, OpenTable, and other top-tier startups. His grandson Tim, perhaps the most eccentric member of the dynasty,2 dubbed the family patriarch the “Grandpa of the VC Industry.”3

Less remembered now is the ür-Draper’s role in shaping the course of history in postwar Germany and Japan. Draper had dipped his toes into geopolitical affairs even before graduating from New York University with both a bachelor’s and a master’s in economics. He chaired a delegation of thirty college students aboard Henry Ford’s Peace Expedition to Europe during the first World War; a quixotic escapade that nonetheless hints at Draper’s formidable networking skills and ambitions. Another interesting signal of Draper’s social sensibilities was his membership in the American Society of Magicians; he “earned part of his college tuition by giving card-trick demonstrations.” Yet despite such capacity for flair, one later profile described him as “soft spoken.” A picture emerges of a man inclined to move through the world through strategic influence— and, perhaps, a bit of misdirection.

After college, Draper served in the Army. Then he led a Reserve division even as he climbed the ranks at a series of investment banks. Although he always had a strong work ethic, Draper doubled down on working night and day during the Great Depression. In September 1929 Draper had “invested his entire bonus in a German-based maker of automatic coffee brewers,” which “soured to zero” in the stock market crash. Draper’s work ethic ultimately earned him a reputation as a “demon for detail and administrative efficiency.”

2. Cometh the Man, Cometh the Hour

In 1940, while Draper was serving as Chief of Staff of a Reserve Division, General George C. Marshall (later of “Marshall Plan” fame) invited him to resume active duty. At first, Draper’s tasks were administrative. He helped write the Selective Service Act and coordinated the mechanics of the draft. But Draper was also a man of action; after Pearl Harbor, he spent a year leading a regiment in the Pacific Theatre. Then an old boss, James Forrestal— an investment bank president turned Secretary of the Navy— poached Draper to develop a common purchasing policy for the Army and the Navy.

Draper’s role in the US military occupation started prior to Germany’s surrender in May 1945. Hot off his promotion to brigadier general at the beginning of the year, Draper was tapped to lead the “economic side of the occupation” by his former procurement boss, General Lucius Clay. Clay was preparing to serve as Deputy Military Governor under General Eisenhower.

3. Behold, the Economic Structure of the Death Star

Congress and various wartime agencies had investigated the structure of Germany’s economy and its “economic warfare” strategies for years by the time Draper touched down in Germany in the summer of 1945.

By then, Germany’s banks, industries, and government had become tightly woven together into a war-mongering singularity that exerted a formidable gravitational pull throughout German society. This did not happen overnight. The path to hyper-concentration pre-dated, and arguably greased the way for, Hitler’s rise to power.

Germany had never adopted an anti-monopoly law like the U.S. Sherman Act to counterbalance its rapid industrialization. However German civil society might have caught up in peacetime, World War I inaugurated a small burst of industrial consolidation thanks to the German military’s procurement policies. After that war, large firms leveraged compensation they received for war-torn properties to buy up smaller businesses that were being ravaged by inflation.

Nor did Germany prohibit cartels. So German industries easily revived international cartel links that were temporarily disrupted by World War I. In 1923, the Weimar government did pass a law restricting certain cartel practices to placate a shrinking middle class— but it was rarely enforced. There were major mergers in that era as well, often between former cartel members.

Soon after Hitler became Chancellor, the Nazi Party hosted a group of industrial leaders to extort political donations that helped Hitler consolidate power even though he did not have an absolute majority in parliament. Fritz Thyssen, the head of the steel combine, personally convened his peers. Because only a few leaders needed to be rounded up in consolidated industries, twisting arms was a quick task.4

In 1933, the Nazi Economics Ministry urged combines to acquire smaller competitors and forced companies to join cartels.5 Many industries such as chemicals, electricity, and artillery became dominated by a handful of large companies. Combines were further entrenched by special tax concessions and subsidies. German combines were not all dragged along reluctantly into following Nazi orders. They often made proactive proposals to abet foreign conquest, and developed business plans in anticipation of absorbing captured foreign competitors into their industrial empires. Several even collaborated with the Nazi regime in perpetrating the Holocaust.

Some members of Congress explicitly attributed Germany’s belligerence to its economic structure. In October 1944, West Virginia Senator Harley Kilgore, chair of a Senate subcommittee on war mobilization, declared in a press conference that:

“The basis for lasting peace is fundamentally an economic one. Germany, under the Nazi set-up, built up a great series of industrial monopolies in steel, rubber, coal and other materials. The monopolies soon got control of Germany, brought Hitler to power and forced virtually the whole world into war.”

Economic warfare investigators found that fewer than 100 men controlled over two-thirds of Germany’s industrial system by sitting on the boards of Germany’s Big Six Banks and 70 industrial combines and holding companies. Germany also dominated a variety of industries internationally through cartel agreements.6

Of course, the “economic side of the occupation” consisted of more than reconsidering economic structure. As Draper recalled in a later interview, the immediate problem facing German industry was that coalmines had been flooded. Without coal production, factories were at a standstill.7 So ramping that production back up to some minimum level was a high priority.8

Yet the situation was not so dire that there was only time to address immediate problems. As Draper himself acknowledged, “[t]he crops that year were quite good, and there was also considerable food we found that the Wehrmacht had stored, which we took over. So there was no immediate danger of starvation that particular fall [of 1945] or even that winter [of 1946].” Food security did become a bigger problem in subsequent years, but during the critical period when the military government took power in Germany, it did not dwarf all other considerations.

In other words, there was time to start tackling the economic roots of the Nazi regime.

So… what happened?

Stay tuned for the next installment.

Primary Sources

Part of my goal with this project is to facilitate renewed scholarship into this era, so I plan to post scans of primary sources to Internet Archive— however, to minimize spoilers, I’ll wait to post some of them (e.g. Draper’s testimony) until later in the series. I’ll also provide a list of some excellent secondary sources.

Lingering Questions

This is an ongoing project, with some threads I have not been able to pursue. Want to help? Here are a few lingering questions:

What would Draper’s NYU economics curriculum have looked like in the 1910s? (What would he have learned about concepts such as monopolies and efficiency?)

How might Draper’s experience with wartime procurement have influenced his views about economic (de)centralization? (And what corporate ties might he have developed in that role?)

What was Draper’s family background? One genealogy site identifies his parents as “Mary Emma (née Carey) and William Henry Draper,” but I have not found detailed information about them. (I recall that another internet source made a reference to the textile industry, but I have not seen confirmation or details on that point.)

Social Media

More ways to follow updates:

Bluesky: Balancecraft

Vichy twitter: BalanceCrafting

Draper and his co-founders blended practices from old money family investment firms with techniques from a new tech-focused, university-centric model that was emerging on the East Coast. (The portfolio was nearly a disaster, with angry investors demanding their money back, until the sons of the founders eked out a market-beating return after extending the end date of the fund by several years. Among other things, this is how the industry learned about deploying funds in tranches, rather than making a single up front cash infusion.)

Tim Draper launched a super-hero themed “Draper University” for tech founders and publicly defended Elizabeth Holmes even after she was sentenced to prison for defrauding investors.

Amusingly, the family photo on Tim’s website looks like the off-kilter second half of a Spot the Difference panel: Succession edition. Surely, in some missing first panel, Jesse’s feet are both clad, Bill’s shades are demurely pocketed, Billy’s vest is neatly zipped, Adam’s collar slouches softly, and Tim’s polka-dotted tie plays it straight down the middle. (One can only speculate how the ür-Draper would have posed.)

As Professor Daniel Crane has written, “[w]hat Hitler needed in 1933 was firms willing to cut the Faustian bargain with ample cash to bankroll his political regime extra-governmentally, an organizational structure spread throughout German society, and the economic power to drive an entire industry at a dictator’s direction. Abnormal financial resources, ubiquitous local presence, and—in particular—the power to direct an entire industry, are attributes of monopoly and cartels. In 1933, the German economy possessed all of these in large quantities due to a course of economic concentration dating back to Bismarck.”

“Combine” was a broad term that encompassed a variety of monopolistic structures. A 1947 State Department publication defined a combine “as an enterprise uniting under common ownership or management competitors (horizontal combine) or producers at several stages in the production process (vertical combine).” Cartels, by contrast, were anti-competitive “contractual arrangements among legally independent enterprises.” Although elements of both forms were used, “the cartel was in a sense a secondary manifestation of the condition in which a relatively few firms controlled a large part of German capital and production. In fields where powerful combines existed the pressure was strong upon all firms in an industry to conform to their policies through participating in a cartel.”

Cartels hurt many U.S. companies, but others saw the glass as at least half full: collusion could help them build and brandish monopoly power against competitors at home.

Most factories were still reasonably intact, despite air bombing late in the war.

There was also political pressure not to ramp production up too much. German peacetime needs would be different than production quotas in wartime, and there was considerable debate about whether Germany could be allowed to enjoy a higher standard of living than countries it had ravaged. Some portion of German industrial facilities was also expected to be dismantled as reparations. Balancing these concerns drove the Economics Division to focus on quantifying “levels of production” that would be allowed going forward.