6. Did the Military Governor Mistake a Main Course for a "Side Dish"?

Where was the military governor while all of this bureaucratic sabotage was playing out? Did he just not understand the goal? Did he regard antitrust as a “side dish”? Was he a pushover? Or corrupt? According to the trustbusters: none of the above.

Recap: Germany’s hyper-concentrated death star economy fueled Hitler’s rise to power, so U.S. postwar policy prioritized economic decentralization. After early leaders resigned, an investigator relaunched these efforts. But several forces threatened to sabotage progress.

The Other Bottleneck Breaker

In 1944, Eisenhower had a problem. Front lines were moving slowly because the few undamaged ports controlled by the Allies had gotten snarled up. One had “literally a hundred ships lying offshore,” but was “unloading maybe two or three a day.” Luckily, he had already borrowed an accomplished engineer from Washington. Once dispatched to Normandy, Lucius Clay quickly diagnosed the problem. Shielding the port commander from micromanagement for just 72 hours dissolved the traffic jam. Hopping from port to port, Clay’s nimble troubleshooting quintupled shipping volumes in just three weeks. Clay made a name for himself, but got yanked back to Washington to serve James F. Byrnes in the Office of War Mobilization, “because he could make decisions rapidly and be arbitrary about them.”

A precocious talent descended from a long line of politicians, Clay lied about his age to enter West Point early. Clay earned good marks for everything but conduct and discipline. Then in the Army Corps of Engineers, he overcame feedback about lacking “tact, judgment, and common sense.”1 During the Great Depression, Clay worked with Harry Hopkins to set up the Works Progress Administration, built support within the Corps for New Deal activities, and literally built a New Deal dam. Clay hoped to lead troops in WWII, but had to settle for becoming the Army’s youngest brigadier general (at age 43) as the nation’s procurement czar.

Will the Real Military Governor Please Stand Up?

In March 1945, victory in sight, Secretary of War Henry Stimson told FDR they should send a “most effective organizer” to handle the “chaotic” situation in Germany. FDR preferred civilian leadership, or making a general-level role for a civilian such as judge Robert Patterson. But Stimson noted Patterson’s “integrity and experience” were needed elsewhere to resolve production problems without scandal. The man to assist Ike “should be a man like General Clay with his ability.” FDR said “laughingly” that “[y]ou will break Jimmie Byrnes’ heart, he is so dependent on him.” After FDR died, Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy argued “strongly” for Clay as a pragmatic short-term move (the military did not want long-term responsibility). With both military and civil service experience, Clay was a “consensus choice.” Clay initially planned to serve only until an expected transition to civilian leadership in June 1946. Although Ike was Military Governor, Deputy Clay handled most day-to-day decisions. Then Ike left to become Army Chief of Staff in fall 1945. His nominal successor, General Joseph McNarney,2 delegated everything other than “military command problems” to Clay. After fraught maneuvering, Clay officially took over in 1947.

What did Clay think of his marching orders? In late 1945, Clay wrote that overall, “JCS 1067 as modified by Potsdam has proved workable… I don’t know how we could have effectively set up our military government without JCS 1067.” One reason he found it “workable” was McCloy’s clever drafting. The order sounded harsh to please Treasury, but included caveats favoring the War Department. A key exception let OMGUS take action to “prevent starvation or such disease and unrest as would endanger” the occupation. McCloy encouraged Clay to use this “escape hatch” liberally. Meanwhile, Clay also exerted influence in Washington. Truman had appointed Clay’s former boss Byrnes as Secretary of State. In 1946, Clay persuaded Byrnes to give a major address adopting “all of Clay’s policy recommendations, sometimes verbatim,” paving the way for elections, a new constitution, and Germany’s admission to the United Nations.

Maybe Clay Just “Never Understood” Decentralization?

But what did Clay think of decentralization? Pondering the plight of the trustbusters, law professor Daniel Crane recently suggested that perhaps Clay “never understood” that “democratizing Germany” was the “long-run policy” aim of decentralization.3

This might have been true at first. Clay had been insulated from Cabinet-level jockeying, and received JCS 1067 only upon boarding the plane for Germany. Clay’s annotated copy of the Potsdam Agreement just bears action-oriented scribbles: “draw up our proposals,” “figure quantities,” and “figure amounts.” Next to a reparations directive: “Lets get busy.” Next to “Allied controls shall be imposed upon the German economy but only to the extent necessary” for various goals: “What is extent?” Next to abolishing discriminatory Nazi laws, Clay wrote: “Legal Is this done?”4

And what about Article 12: decentralization?

“Our cartel proposal.” A bit glib! Clay’s remarks at a staff conference in August 1945 also do not evince deeper understanding. In one speech, Clay summarized OMGUS aims as de-Nazification and de-militarization. In another, Clay announced an “endeavor is to live in a goldfish bowl.” Neither speech mentioned decentralization.

Dawning Awareness

Yet despite an initially blinkered view, Clay had already taken a major concrete step. In June 1945, Clay proposed taking over Farben “until Allied Control Authority determines the disposition to be made of these plants, with the view to the final and complete dissolution.” This would “convince the doubters that we mean business with respect to the large cartelized German combinations.” Then Ike ordered “dispersion of the ownership and control” of plants and equipment not otherwise destroyed.

Perhaps Clay thought of Farben in terms of war capacity, and let tensions with early decentralization leaders distract him from the bigger picture. But it’s unlikely Clay stayed ignorant for long. The Allies began drafting a competition law soon after Potsdam. At first, they seemed poised to adopt bright line thresholds to initiate proceedings against Germany’s hyper-concentrated firms. This “mandatory” approach would use readily measurable metrics, such as number of employees or revenue. The State Department authorized Clay to “accept as a final resort such a provision relative to the percentage of an industry which could be concentrated in a single corporation.” Clay sought help to avoid a “decartelization law without teeth”: “We have little hope that a law without mandatory provisions would be really effective as each separate case would require quadripartite agreement.” In any event, there is little doubt Clay understood the mission by October 1946– when Clay rebuked Draper.

That Time Pythias Wrote Damon a Stern Memo

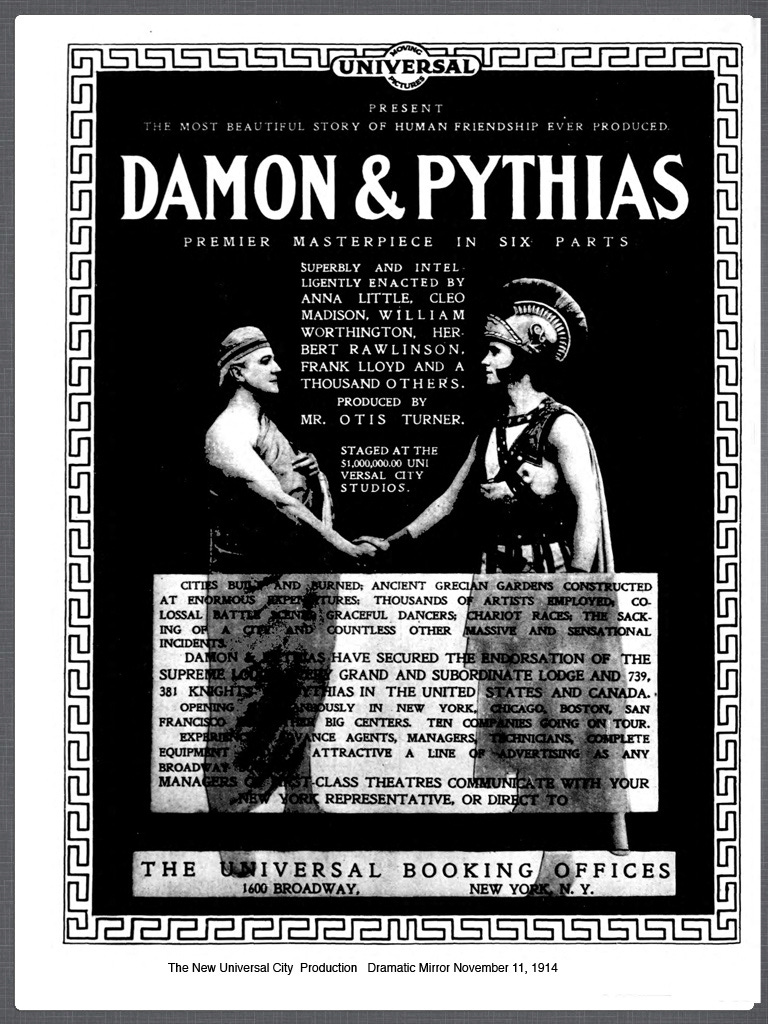

Clay did not surround himself with “yes men.” He preferred smart, driven men with strong opinions. Men like Draper. As Clay worked round the clock, Draper kept pace. Years later, Clay told Draper he “made possible anything I may have accomplished” in Germany. Draper responded: “Damon will never forget Pythias”–referring to a Greek legend about friends willing to die for each other. But they did not always agree.

While Draper had far more facetime, Martin managed to build good rapport with Clay as well due to a loophole in the org chart. Besides serving as Decartelization Chief (under Draper), Martin also served as Farben “Control Officer.”5 For that special project, he reported directly to Clay. That let him advocate for his team.

Clay was as nonplussed by Draper’s rogue propaganda to visiting news editors and other wildcat actions as he had been by leaks about inadequate de-Nazification. So he issued a memo reprimanding Draper. Decentralization was not a fair scapegoat since it “had not progressed sufficiently… to have any real effect on the German economy.” He was “certain that the revival of democracy in Germany is dependent on our ability to develop an economy which is not controlled by a handful of banks and holding companies.” Clay then cannily held a live “gripe session” where he solicited dissenting opinions as an opportunity to chew out Draper in front of the staff. Clay was “personally… in sympathy with decartelization based on size until we have destroyed the conditions which did exist in Germany” and “absolutely convinced” the “choice in Germany” was “between free enterprise of […] small business and socialism.” Draper protested that “Germany in the accredited world markets, which it is going to have to enter, has got to have the opportunity to have efficient industrial organization; and where that requires sizable industry or plants, that should be permitted.” Clay reminded Draper of his duty as an officer to follow official U.S. policy. Documents about this incident made their way to the Senate, as well as The New York Times.

The Tail That Wagged

There were limits to how much Clay was willing to rock the goldfish bowl. Despite Martin’s requests, Clay declined to give his team Division status. But Clay had stood up for them in no uncertain terms to make Draper’s men fall in line. Draper even said he had his “tail between [his] legs.” So things were about to get way better, right?

Stay tuned for the next installment to learn more…

Primary Sources

Featured newly-scanned primary sources: 1) Excerpts of Clay’s Potsdam annotations; 2) Clay’s Aug. 1945 OMGUS staff speech; 3) Clay’s less rousing “goldfish bowl” speech on recordkeeping; 4) Clay’s Oct. 1945 memo on expected transition to civilian control; 5 Clay’s memo rebuking Draper.

A biographer later wrote that an “equally willful New England banker” (hmmm, who could that be?) called Clay “the most arrogant, stubborn, opinionated man I have ever met.”

On October 6, 1945, McCloy wrote McNarney: “After long struggle and painful recruiting we formed a staff composed of sincere, good and efficient men to help Clay” and that “Clay has only recently been able to get… free of the need for persuasion down through the army commands.” His diary entry noted Clay was “not happy over Eisenhower’s proposed successor.” (For purposes of this story, Clay always functioned as “the Military Governor.”)

As noted previously, I am not linking to anything with significant spoilers until later in the series. (If you don’t mind spoilers, you can easily find it online despite Google’s decay).

Some things never change.

Draper claimed he was the one who originally proposed that dual role (back when he viewed decentralization as just one among many problems). #Irony!