12. "Dale Carnegie in Reverse"?

What economic views did ordinary Germans have after the war? Were they even aware of America’s plans to introduce economic democracy hand in hand with political democracy? If so, what did they think?

Any effort to inform the German public about the goals of economic reform would have to take into account that the Germans were not a blank slate. They had just lived through one version of socialism under the Nazis– albeit one with some ideological contradictions.1 Some Germans would also have been familiar with existing economic systems and emerging movements elsewhere in Europe. They were less likely to have any prior familiarity with the American antitrust tradition. So outreach would be key.

Recap: Germany’s hyper-concentrated death star economy fueled Hitler’s rise to power and the outbreak of WWII, so U.S. postwar policy prioritized economic decentralization to parallel democratic political reforms. Yet on the ground, General William H. Draper, Jr. recruited bankers and big businessmen to run the “economic side of the occupation.” After the first two decentralization leaders resigned in frustration, an experienced investigator was brought in. Alas, forces both inside and outside military government were thwarting progress even though the military governor understood the importance of decentralization. Another Allied Power shared some blame for gridlocked negotiations. Then the midterm elections of 1946 shifted the balance of power domestically. In the summer of 1947, two leaders abruptly departed Germany: the biggest roadblock to reform and the strongest advocate for it. Without them, would reform get back on course– or further derailed? It turns out a patent lawyer’s love life might have played a role. German officials had mixed views, while some academics developed compatible views.

“People Were Talking Socialization”

Germans did not hesitate to express their preferences, even in defeat. Just a week after the Nazis surrendered, German trade unions demanded that all coal mines be socialized. In September 1945, a trade union federation in the Soviet Zone formally proposed that heavy industry be socialized. The following year, the Social Democratic Party advocated socializing all property confiscated by the Allies– other than small and medium businesses– as a step toward a democratically planned economy. By socialization, SDP meant self-governing organizations with labor serving on boards, rather than state ownership. SDP believed that dissolution would only be a temporary fix, because capital would simply reconstitute into new big business combinations.2

The Americans had been apprehensive about collectivism even before World War II began. In 1938, after FDR urged Congress to address concentrated private economic power, Solicitor General Robert H. Jackson gave a speech contending that economic concentration paved the “road to socialism.”

After the war, OMGUS leadership observed German sentiment with concern. General Clay told staffers in October 1946 that he believed Germany “must have small ventures, or we will find our ventures will be affected by influence of Communists, and the influence of the British Labor Party [which increasingly favored nationalization of heavy industries] in the British Zone.” Rising tensions with the Soviet Union– which encouraged collectivism in its Zone even as it seized certain German property for itself as reparations– heightened American concerns.3

There were some German leaders who publicly echoed American views favoring decentralized free enterprise. For example, in August 1946, Konrad Adenauer, gave a speech to the Christian-Democratic Party (CDU)’s Congress warning that “[t]he concentration of economic power in the hands of a few, whether private or public, is a danger to the political freedom of the individual as well as of the people as a whole.” Yet he also advocated a “mixed-economy,” where, for example, private capital might have a minority stake in a mining operation, while the majority of shares would be split between workers and local government.

When Herman Abs, Deputy Chair of the German Reconstruction Loan Corporation, was asked a few years later whether the German public generally “favored socialization or whether they favor individual initiative,” Abs hedged that “[i]t depends very much on how it is stated and presented to the public. If there should be a plebescite, I should say today that rather the majority is inclined to socialization. But if all facts could be stated properly and carefully it might be different.” Even though the CDU was “in principle not in favor of socialization,” he predicted that a vote on the topic might “split the party.”

In October 1946, the French-occupied state of Hesse voted in favor of a new constitution that banned “the abuse of economic freedom, in particular [if used] to accumulate monopoly power”– and required all “property that harbors the risk of such abuse” to be “transfer[red] into common property.” Further, it specified a wide range of basic industries including coal, iron, steel, potash, and transportation that would be subject to common or public ownership. The CDU and the liberal Free-Democratic Party challenged this charter in court. Meanwhile, General Clay “insisted on a separate referendum” to stop (or at least forestall) that outcome. When that referendum passed, Clay “decided to withhold approval of the Landtag’s implementing legislation” at the Allied Control Council. Outraged SDP leadership analogized these actions to the Nazi Party’s anti-democratic coups against the Weimar Republic.

As this dispute played out, two more states, both in the British Zone, enacted socialization laws. Although there were detractors who preferred capitalistic private property rights, they were outvoted. In any event, the British ultimately fell in line with OMGUS, by agreeing to punt the question of socialization until the Germans had their own fully sovereign federal government.4 The United States later made Marshall Aid to West Germany conditional on deferring socialization.

OMGUS Outreach: A “Dale Carnegie in Reverse”?

One economist–who was not part of Draper’s clique, but instead worked within the Decartelization Branch–was particularly outspoken in favor of outreach efforts to the German public. Originally from Kansas, Charles Dilley had worked as a school superintendent before earning a master’s degree in economics and teaching economics at a military academy.

Dilley was hired to lead the Consumer Goods Section in April 1946, and within a year was promoted to serve as an assistant chief of the Decartelization Branch. Dilley supported Law 56 and largely embraced official decartelization and deconcentration policies in general–although he had spirited debates with lawyers who came from the antitrust division about how to implement those policies without impairing technological or engineering efficiencies.

In September 1947, Dilley wrote to then-chief of the Decartelization Branch, Phillips Hawkins, noting that he been “rather active in this field [of outreach to Germans] for the past year and a half” and was “keenly interested in it.”

Ordinary Germans were susceptible to collectivism, Dilley feared, because they had not been educated about any alternative. “Everywhere I went around here at first, particularly among Germans, people were talking socialization,” and that was naturally concerning, in his view, because the “Socialist” Nazis had rearmed Germany. “Every argument that can be used to justify holding-company empires,” Dilley wrote, “can be turned to justify the socialistic programs. If business organizes itself into a nest of private collectivisms, it will have little argument against establishment of an overriding public collectivism.” Dilley linked the mission of “establish[ing] a democratic, peace-keeping Germany” with promoting a “capitalistic Germany with as large a healthy middle-class as possible.”

But Dilley was not sure OMGUS had settled on a consistent philosophy to communicate. If OMGUS “conceive[s] of [its] program as an honest, straight-forward, antitrust, antimonopoly program,” Dilley believed “we may fairly expect honest and sincere German decartelizers to get behind it.” Germans would not accept a program they view as “punishment.” Other parts of OMGUS—the “War Crimes people, Denazification people, Demilitarization people, Reparations people, etc.”—would “deal out the punishment for Germans.” The Decartelization Branch “should honestly stress that we have no intent or desire to atomize (pulverize) German industry: that our purpose here is not to permit the rest of the nations of the world the benefits of large-scale production, but to punish Germany by denying those benefits to her, thus crippling the German economy and making the international markets café for American big business interests.” Dilley was optimistic that OMGUS could “defend (and sell to the German people) a deconcentration program on antitrust, fair opportunity, free enterprise, fair trade grounds, if it actually has these ends as its honest aim.” Dilley contended that, instead, “[t]oo often we have talked as if we were determined to atomize German industry.” Accordingly, he thought OMGUS had accomplished “a Dale Carnegie in reverse,” putting into practice the techniques of “How to Lose Friends and Alienate People.”

Yet in later testimony, Dilley could name only one person in the Decartelization Unit he personally witnessed taking an extreme position about “deconcentrat[ing] everything” such as “set[ting] the railroads up as little individual competing railroad lines.” This lieutenant colonel was eventually relieved of duty by Hawkins, but perhaps because the encounter happened soon after Dilley joined OMGUS in April 1946, it made a “lasting impression” on him. Dilley admitted that he could not recall Martin or Hawkins or other OMGUS leaders advocating any “ruthless action, pulverizing or atomizing.” Moreover, Dilley spent some time with fellow economists in the Economics Department, who were prone to fomenting caricatures and mischaracterizations about the Decartelization Branch, both within OMGUS and in communications with outsiders.5 In any event, Dilley viewed Law 56 itself as “moderate” and “sensible.”

Ordinary Germans were not completely in the dark about OMGUS’s plans to promote free enterprise. For example, an August 1948 German news article reported that OMGUS would be taking action against groups including the “scrap-iron dealers, the shoe-manufacturers, the truck manufacturers and the producers of mining equipment, that had intentionally or not” thwarted post-war free enterprise through price-fixing, which could be penalized by a fine and even imprisonment. Another article noted that “[t]he principle of an open competition is to be maintained at all events, and the Military Government will severely interfere against every attempt to evade these regulations.”

But apart from such dispatches, OMGUS fell short in communicating the overall goals and philosophy behind its planned economic reforms. This was likely due in part to a shrinking budget, as a Republican-controlled Congress sought to slash costs. Even when the Marshall Plan gained steam, that did not translate into more funding for outreach.6

If Not Talk, Then Action?

Winning over Germans without a comprehensive messaging program would be challenging– but perhaps not impossible. If the Decartelization Branch could take legal action to demonstrate how economic decentralization worked in practice, that would deliver concrete results that could persuade the German public (and quell internal critics).

There was even low-hanging fruit that would take minimal resources to implement: OMGUS could start by simply eliminating Nazi-era occupational licensure requirements. Many Germans still could not open up a new business, such as a watch repair store, without first navigating a crooked licensure process controlled by local cartels and monopolies, which were often Nazi-affiliated. The Decartelization Branch received “hundreds of complaints from independent German businessmen that although their plants were ready to operate, they had been refused the necessary license.” Nixing these restraints would give ordinary Germans the experience of free enterprise.

Moreover, despite personnel cuts, the Decartelization Branch still had sufficient resources for Hawkins to organize four teams to launch investigations into various major combines in June 1947. According to Dilley, Hawkins “was in a terrific hurry,” giving the teams an initial deadline of about 10 weeks. Each team was tasked with putting together not merely an extensive study of their assigned combine, but also a “deconcentration plan outlining specific subsidiaries and plants to be divested and then a draft directive to the company to give effect to that deconcentration plan.” Dilley had expressed concern that Germans could “no more conceive of Siemens & Halske [an electrical engineering combine] as an evil doer than can the average American conceive of General Motors as an evil doer. They consider such corporations one of the sources of Germany’s strength and greatness.” This initiative would tackle not only Siemens & Halske, but also three other combines.

So, how did the Decartelization Branch fare in taking action?

Stay tuned for the next installment…

Primary Sources

Below are newly-scanned primary sources relevant to today’s installment:

Letter from Charles Dilley to Ferguson Committee member A.T. Kearney re: "Transmittal of Memoranda Dealing With Winning German Support for the Decartelization Program," Dec. 13, 1948, https://archive.org/details/dilley-German-support

Letter from economist Charles Dilley to Chief Phillips Hawkins re: "Mr. Avery's Proposals for the Deconcentration of the Henschel Combine," Sept. 18, 1947, https://archive.org/details/dilley-henschel

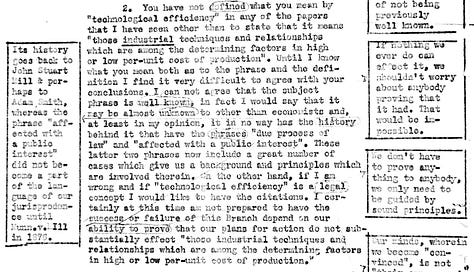

Letter from Johnston Avery to Charles Dilley debating “technological efficiency” as a metric for deconcentrating German combines, Sept. 19, 1947, https://archive.org/details/avery-dilley-efficiency

Letter from Charles Dilley to Johnson Avery re: Clarification of Policy Statement, Sept. 22, 1947, https://archive.org/details/dilley-avery-efficiency

Letter from lawyer Creighton Coleman to economist Charles Dilley, with response typed on the same letter, https://archive.org/details/dilley-coleman-debate

Memo from Charles Dilley to Phillips Hawkins, “Explaining Decartelization to the Germans,” Sept. 10, 1947, https://archive.org/details/dilley-educate-Germans

Part of my goal with this project is to facilitate renewed scholarship into this era, so I plan to post more scans to Internet Archive—however, to minimize spoilers, I’ll wait to post some of them until later in the series. I’ll also provide a list of some excellent secondary sources.

Although the Nazis did maintain some public ownership, they also re-privatized firms that the state had taken over during the Great Depression, and ultimately sold off publicly-owned firms from “a wide range of sectors [including] steel, mining, banking, local public utilities, shipyards, ship-lines, railways, etc.” The Nazi Party may have taken this course to “win support for its policies from big business” and to “increase[ ] revenue and expenditure relief for the German Treasury.” A prime example of the former was the decision to re-privatize United Steel Works– a very favorable outcome for industrialist Fritz Thyssen, one of the earliest major supporters of the Nazi Party. See Germa Bel, Against the mainstream: Nazi privatization in 1930s Germany http://www.ub.edu/graap/nazi.pdf

Much of the background on the attitudes of German political parties here comes from the Princeton University history department dissertation of Liane Hewitt. A synopsis of the work is available at Hewitt L., “Monopoly Menace: The Rise and Fall of Cartel Capitalism in Western Europe, 1918–1957.” Enterprise & Society. Published online 2024:1-23. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/enterprise-and-society/article/monopoly-menace-the-rise-and-fall-of-cartel-capitalism-in-western-europe-19181957/762EF05674DAB85AA9FAE07AE1723B37.

Anti-communist sentiment accelerated in the U.S. after Republicans gained control of Congress (for the first time since 1931) in the 1946 midterm elections. Domestically, President Truman responded by launching a commission on federal employee loyalty, which culminated in a March 1947 executive order starting a loyalty program to root-out suspected Communists from federal government. See Truman’s Loyalty Program, Harry S. Truman Library, https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/education/presidential-inquiries/trumans-loyalty-program

The French, meanwhile, shifted towards calling for internationalization: stripping the Ruhr-Rhineland area from Germany altogether, and instead instituting international ownership of the heavy industries there.

As for whether American business interests impeded deconcentration and decartelization, Dilley testified that “any adverse effect that businessmen or organizations had on our programs so far as I know or have reason to believe was an indirect one due perhaps in part to the fact that many businessmen may have thought we were wild-eyed radicals and that we were out to smash everything in Germany.” Dilley also rejected the suggestion by Hawkins’ successor, Richardson Bronson, that the Branch’s work was universally disapproved of by everyone other than the Decartelization Branch and General Clay: “I believe we had some friends around over OMGUS in almost every branch and divisions. Too many people went out of their way to call upon us and say, ‘look, what about such and such a cartel situation.’ There were sincere decartelizers who really believed in the traditional anti-monopoly philosophy of the U.S.”

Americans did at least make a concerted effort to ensure that German children could eat ice cream at their Christmas parties. See “Ice Cream for Germans Saved,” New York Times, Dec. 22, 1947 (“Christmas ice cream for more than 100,000 German children was rescued from melting on the United States army transport […] The ice cream was purchased with part of a $24,000 fund raised by Americans in this area to provide 250 Christmas parties for German children. The Alexander’s refrigeration system broke down while she was en route from the United States, so seamen diverted cold water from the ship’s water cooling system into the refrigeration pipes.”).